Few saw the Chromebook coming. When it launched half a decade ago, the category was broadly maligned for its limited feature set, middling hardware specs and operation that required an always-on internet connection to work properly. But things change in five years. In 2015, the category overtook MacBooks in the U.S. for the first time ever,

selling around two million units in Q1. It’s a pretty astonishing number for a product many pundits deemed doomed in its early stages. And that victory has been largely fueled by the K-12 education market.

Recent numbers from consulting firm

Futuresource paint a similar picture, with Google commanding 58 percent of U.S. K-12 schools. Windows is in second with around 22 percent and the combined impact of MacOS and iOS are close behind at 19 percent. It’s a rapidly shifting landscape. Three years earlier, Apple’s products represented nearly half of devices being shipped to U.S. classrooms.

Now some of the biggest players in technology are poised to make a new push into education. Last month, Apple released a newly refreshed version of its Classroom app, coupled with its

lowest priced iPad ever. In January, Microsoft announced plans for a low-cost laptop, coupled with cloud-based software. In a week, it’s

expected to unveil its next big move at an education event in New York, aimed at going head to head with the Chromebook.

For many schools, the dream of a one-device-per-child experience has finally been realized through a consumer technology battle waged by the biggest names in the industry. Over the past decade, Google, Apple and Microsoft have shaped the conversation around technology in schools, but as ever, none are in agreement on a one-size-fits-all approach. One thing all the players seem to agree on is that education is a market well worth pursuing.

The kids can’t wait

Education had always been an essential part of Apple’s DNA. The company saw the value of bringing its devices to the classroom almost immediately. Steve Jobs saw the wide-ranging potential of the school market early on. Two years after Apple was founded, it scored a contract to bring 500 computers to Minnesota schools.

“One of the things that built Apple II’s was schools buying Apple II,” Jobs said in

a backward-looking interview from 1995. “We realized that a whole generation of kids was going to go through the school before they even got their first computer so we thought the kids can’t wait. We wanted to donate a computer to every school in America.”

Both Apple and Microsoft flourished in the computer lab models. But even with education discounts, their respective desktops were still fairly pricey — expensive enough to make the dream of providing every student with their own system a distant pipe dream.

“You could get 20 or 30 [computers] for the school, but you couldn’t get one for every student,” IDC analysts Linn Huang tells TechCrunch. “And then netbooks came around and blew up in education. A lot of the reason is because this was the first time we put affordable hardware in front of buyers.”

When they arrived on the scene in 2007, netbooks were a breakthrough technology; they were rugged, light and, most importantly, affordable, a perfect combination of traits for cash-strapped school districts. They were also an important driver in the growing early 21st century drive to make technology in K-12 classrooms a more one-on-one experience.

Initially, netbooks’ reign was as short-lived in the classroom as it was in the consumer market. The price was right, but the hardware wasn’t. The keyboards were sub par, the screens were bad and processing just crawled. Just as educators and the public began to sour on the notion of netbooks, Apple arrived on the scene and filled the hole perfectly.

The rise of the iPad

From the outside, it seems that the iPad’s success in education was something of a happy coincidence for Apple. That’s not to say, of course, that the company didn’t see the educational potential in the “magical” piece of glass and metal. It promoted apps like “The Elements” from the outset, as it worked to convince a still-skeptical press that its new offering was more than just a big iPhone.

And as Phil Schiller would put it,

addressing a crowd at an event a few years later, “education is deep in Apple’s DNA.” That aspect had never left the company, as a generation who grew up using Apple IIe and Macintosh units in computer labs began making computer-purchasing decisions of their own.

But while education wasn’t the primary focus in the launch of the first iPad, the potential for the devices as part of classroom curriculum came into sharp focus as the limitations of netbooks became painfully clear. iPads offered a premium hardware experience, and with a starting price of $499 retail, they weren’t exactly cheap, but were certainly comparable to some netbooks.

They were also a heck of a lot cheaper than Apple’s own laptop offerings, and likely cannibalized shipments of much pricier MacBooks to schools, though, as Cook happily

pointed out at the time, they appeared to be doing a lot more damage to

Windows PCs in the space.

Excitement around iPads in education hit a fever pitch in 2013, when the Los Angeles Unified School District announced an incredibly ambitious play to put the devices in the hands of all its students, for a total of around $1.3 billion. That deal

ultimately ended in disaster, thanks to questionably preferential treatment and unfinished software from education publishing house Pearson.

Stumble aside, Apple continued to utterly dominate education. Slates had eclipsed netbooks in the education sector, and by the company’s own estimates, iPads controlled around

94 percent of the tablet market in that space. But another contender had been waiting in the wings, ready to turn the entire segment on its head.

The coming of Chromebooks

In a perfect world, price would be no object when it comes to education. But back here on planet Earth, it’s a key factor in the decision-making process for the IT departments that do most of the device purchases for schools and districts.

But the story of the Chromebook isn’t simply one of undercutting the competition. If that were the case, netbooks might still have a place outside of junk drawers. The rise of iPads (and to a lesser degree, other tablets) in the educational space revealed many teachers’ desires for additional inputs. For all of their early constraints, like limited offline functionality, what Chromebooks have always offered is a complete hardware solution, including a full-size keyboard.

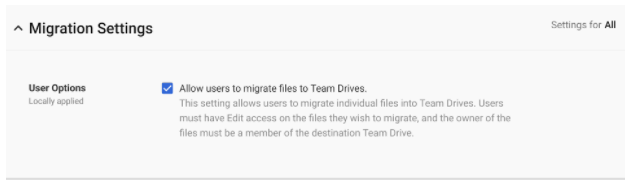

Even more importantly, the devices’ software was designed with large-scale deployment in mind.

“Google is really the perfect nexus of, yes, the hardware is cheap,” says Lin, “but where they’re really winning the market is the Google for Education console has really been fantastically received and has made it possible for IT administrators to manage profiles on individual machines or manage multiple students on one machine.”

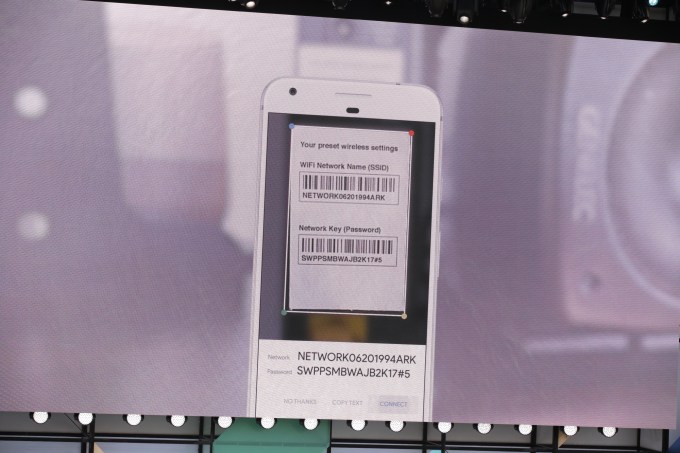

Cyrus Mistry, the head of Google’s Device and Content for Education, tells TechCrunch that wide-scale implementation was part of the platform’s appeal from the outset. Even as the devices largely flew under the radar of mainstream consumers, institutions saw value in the time-savings the new class of devices presented. And if one is lost or stolen (a common problem in schools), they can be disabled remotely.

Mistry was a part of the Chromebook team in its earliest days, tasked with handing the company’s pilot Chromebook model, the

Cr-48, to business and schools. He says that IT departments at least understood the value proposition immediately. “To enroll a Chromebook, right, you hit Ctrl+Alt+E, and that’s it,” he explains. “It’s enrolled forever into that domain of that district. And that is the whole process. It takes about six seconds.”

Chromebooks turned a corner in 2013, when they became the fastest-growing segment of the PC market, thanks in part to the company’s ongoing efforts to seed them to school districts

and other markets and manufacturing partnerships with big-name PC vendors like HP and Lenovo.

By fall of 2014, Chromebooks

had overtaken iPad shipments in the educational sector for the first time. In all, the devices had managed to wrestle away 20 percent of the education market in the U.S. And just about this time last year, the once-maligned category outsold Mac OS devices, driven largely by K-12 education

here in the U.S.

The Chromebook’s popularity in education outside the U.S. has been more elusive, though the company has turned a few corners in recent years. “Google’s footprint everywhere else is limited,” says Huang. “Some other regions, particularly in Western Europe, we’re starting to see some ramp up. But again, we’re still largely talking about a U.S. story today.”

But the company is starting to make a dent in places like the U.K. and Sweden. Naturally, Mistry is optimistic about the category’s growth in other markets. “As soon as a country realizes how good these are, it goes up very fast,” he says. “We talk internally about our track record for pilots. Like if we put in a pilot of Chromebooks into a district and say look, ‘don’t trust us (like I was saying earlier) just try the product out.’ ”

Much of the issue with adoption abroad can be chalked up to poor Wi-Fi infrastructure in schools. While current Chromebooks are certainly more capable of functioning offline that earlier models, connectivity is still key to functionality. Google also has made the most inroads in places where it’s done direct outreach. It’s far easier to get a district to invest money in a fleet of machines once it’s actually seen them in action.

Of course, markets and individual demands from products vary greatly from market to market, but Google’s gone a ways toward refining and broadening the scope of the category. It recently ported Android’s Play Store over to a number of devices, which products like Samsung’s newly released Chromebook offer unique takes on the space with things like pen inputs.

But while the Chromebook has seen surprisingly rapid growth after a couple of years of failing to meaningfully move the needle, the company won’t be expanding into any new markets without a fight, as two perennial edtech heavyweights gear up for their own next steps.

A more populist iPad

“I think the iPad is still the best device, especially if you want to do real work,” Eric Anderson, the director for Ed Tech at Archbishop Mitty High School, tells TechCrunch. The San Jose private school has long been held up by Apple as a real-world example of what iPads can do in education. It’s a true one-to-one experience, with devices handed out to students the week prior to the beginning of the school year for use in the classroom and the home.

As the school writes on its iPad FAQ, no students are allowed to opt out of the program, as “the benefits of a tool like this can only be achieved if the tool is used by all students.” Anderson adds that he believes that Chromebooks were widely adopted by schools for “the wrong reasons,” as a solution for wide-scale deployment during standardized testing.

“You just sign into an account and you’re done,” he says. “While the Google apps are very powerful, you’re limited in what you can do in a web browser. The iPad is a more full-featured experience that allows you to be creative and produce high-quality work. Plus it’s a nicer form factor.”

It’s easy to see why Apple has held the school up as a prime example of iPads in education done right. Five years after it started the pilot program, the school remains committed. Of course, a 1,700-student Roman Catholic private school isn’t exactly representative of U.S. educational institutions. Rather, it’s a pretty solid metaphor for Apple’s approach to the space this far.

The company has long insisted upon quality over quantity, and focused on individual impact over volume in the classroom setting. In a sit-down

interview with BuzzFeed back in 2015, Cook’s take on the Chromebook echoes that of Anderson’s, going so far as referring to them derisively as “test machines.”

“We are interested in helping students learn and teachers teach, but tests, no,” he said. “We create products that are whole solutions for people — that allow kids to learn how to create and engage on a different level.”

Two years after that interview, the Chromebook’s success does appear to have had a measurable impact on Apple’s own education play. It’s hard to say precisely how much Google’s play has influenced Apple’s decision making in the space, but the company certainly seems newly invigorated of late. Last year, the company

introduced Classroom alongside its iOS 9.3.

The app received little in the way of fanfare from the tech press, because it was released alongside more mainstream updates like Night Shift. But Classroom brought some much needed control to Apple’s tablets, offering teachers an overview of an entire class’ worth of screens at once. The app also brought a simple log in system for multiple student accounts, so iPads could be returned to teachers at the end of the day, a more cost-effective solution for those schools that simple don’t have the financial coffers of an elite private school.

Last month, the company made a few strategic moves that also got buried amidst other announcements. Rather than introducing a brand new iPad, the company made some tweaks to the line and dropped the price by $70, to its lowest price ever.

The move was seen as an attempt to drive consumer demand in a space that had stagnated, but the new model also meant a $300 price tag for schools, putting it more in line with Chromebook pricing. The company also partnered with Logitech to produce a school-only ruggedized iPad case. And Apple also introduced the 2.0 version of the Classrooms app, bringing even more control to the iPad’s software offering.

“What makes iPad such a strong tool in the classroom is the unique combination of hardware, software, services and apps that only Apple can deliver,” Apple VP Susan Prescott said in a comment offered to TechCrunch for this piece. “Teachers are using Apple technology to engage students in innovative new ways, making education more personal, interactive and impactful. We’re incredibly passionate about education and are focused on empowering students, teachers and schools to get the most out of these powerful learning tools in the classroom.”

A return for Redmond

Like Apple, Microsoft was an early beneficiary of the school computer lab model

during the 1980s. IBM systems served as a perfect backdoor for the DOS operating system produced by a 32-person software startup out of the Pacific Northwest. The company maintained that foothold as DOS made way for various flavors of Windows, while applications like Word and Excel became essential productivity tools for schools and offices alike.

Windows’ ubiquity also helped the company ride netbooks to some classroom success outside the computer model. Since then, however, the software giant has seemingly had some trouble finding its way. While Chromebook’s most notable impact has been on the iPad — at the time a leader in the education space — the category is more in line with budget laptops that have been such a key part of the company’s growth.

Microsoft still maintains a lead globally, courtesy of low-cost hardware, but Chromebooks have taken control of the market here in the States and are poised for growth globally, as Wi-Fi becomes more ubiquitous on school campuses and the company pushes into more form factors. Surface’s premium price point, meanwhile, has proven a difficult barrier for educational adoption. Asked how the growth of Chromebooks has impacted its bottom line, the company points to its global successes and recent initiatives like

Minecraft: Education Edition, while discussing overall strategies beyond devices.

“Our vision encompasses a holistic learning experience, not just devices,” Anthony Salcito, Vice President of Worldwide Education tells TechCrunch. “The competition that matters to us in the education sector is the competition for talent faced by employers and countries dealing with a modern and changing workplace. What’s most important to us is how educators and students use technology to make their learning environments better — we are driven to help students achieve more in this new world.”

But while both Apple and Microsoft are sticking to their guns as far as their respective strategies toward education are concerned, it’s hard to deny that Google’s recent success has played a role in dictating recent decisions by both companies. For Apple, it’s a pricing drop, paired with a more comprehensive software package on iOS.

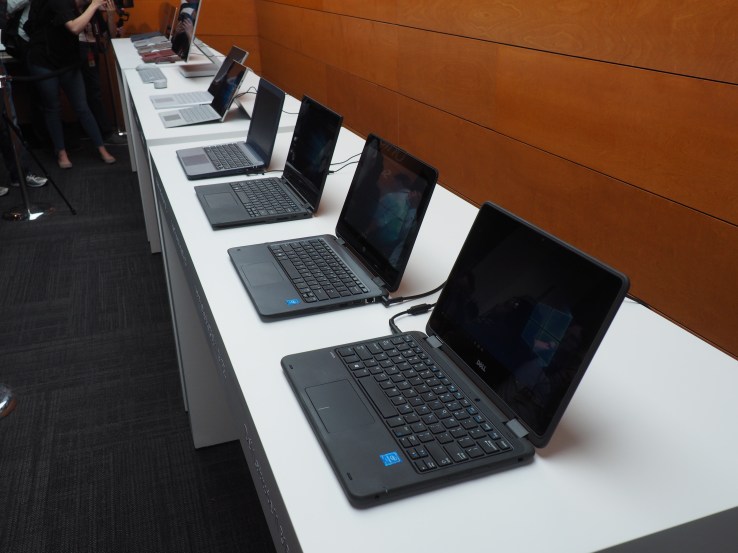

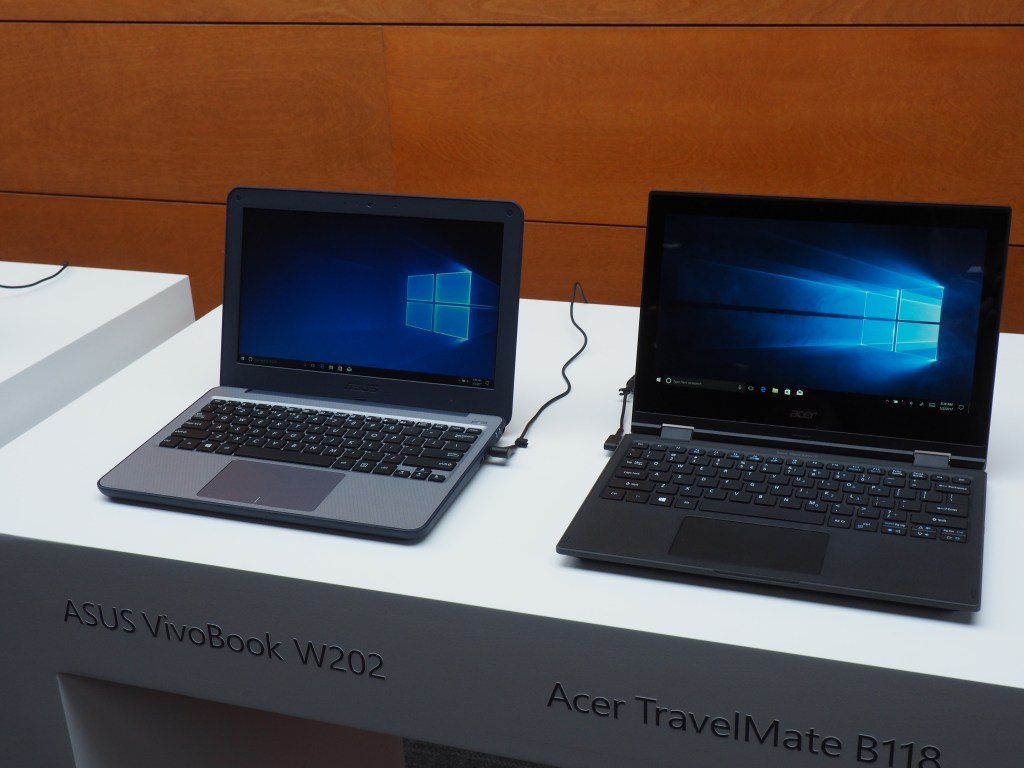

Microsoft’s own moves, on the other hand, are poised to take on Chromebooks more directly. The company is seeking to win back some of the low-end educational PC market. It recently announced Intune for Education, a device management system that certainly had echoes of Google’s offering, particularly when coupled with plans to launch aggressively priced educational PCs by manufacturers like Acer, Dell, HP and Lenovo, starting at $189.

The company is also expected to take the plan a step further next week at an education event in New York City, with the launch of Windows 10 Cloud, which may highlight the launch of systems designed specifically to beat Google at its own game. Certainly Microsoft has a number of things working in its favor, among them its productivity software, which continues to have a strong presence in spite of the growth of expanding feature set of Google’s G Suite.

“We’re working hard with device providers and third-party software providers to build the right experiences for schools, educators and students — devices that are affordable and functional for the environments that we need inside of our school today,” Salcito continues. “For our own products, we work closely with thousands of educators and students and their feedback will continue to drive the evolution of Windows 10 and Office 365 so that our products can best address schools changing needs.”

The company’s strong global foothold in the space is also a solid building block for its newly reinvigorated push into education. After all, devices may need to be refreshed every couple of years or so, but what school district wants to keep switching operating systems every few years? Perhaps if the company can offer a compelling alternative, it can stem some of Google’s explosive growth domestically and cut off at the pass the Chromebook’s international push.

The battle for the classroom

The fight for classroom technology has ebbed and flowed quite a bit over the decades. Thus far, 2017 has proven a high-water mark, courtesy of the explosive growth of Chromebook category. Both Apple and Microsoft have made announcements this year, designed, in part, to recapture some of the market share they’ve lost to Google’s cloud-based hardware offering.

Google, meanwhile, has already broadened the scope and usefulness of its devices, a far cry from the first Chromebook models. And there are new form factors likely just over the horizon. The company is also expected to make an even more aggressive push outside of the States, where Microsoft easily has the largest foothold.

Ultimately, the educational sector isn’t all that different than the consumer space. Increased competition has led to better and cheaper devices, ultimately benefiting the end users. Brand loyalty plays a big role, as well — once a school or district has opted into a device, it’s easier to simply stay put, rather than ripping it up and starting again.

Apple and Microsoft have both played fundamental roles in shaping technology in the classroom, dating back to the early days of computer laptops, while Chromebooks, iPads and cheap PC laptops have helped many schools realize the dream of a one-to-one hardware experience in the classroom.

Of course, this support of young minds isn’t entirely altruistic. Fostering an entire generation of first-time computer users with your software and device ecosystem could mean developing lifelong loyalties, which is precisely why all this knock-down, drag-out fight won’t be drawing to a close any time soon.

For the most part, companies are taking different, but overlapping approaches to the space. Taken as a whole, competition and breadth of scope will help serve the greater good of getting more devices in the hands of students, while letting the IT departments that make purchasing decisions hopefully choose the devices and ecosystem that best suits their individual needs.

For the time being, here in the U.S., at least, Google has won the battle for market share. But the war is far from over.